Helping your children master writing skills presents a challenge when working with different learning styles. When I taught freshman English, my students were allowed to choose their own approach for planning. Some just made lists of questions while others constructed graphic organizers like bubble charts or word webs. They usually found ways to adapt the process to their own learning styles. But I often wondered how I could adapt the planning stage for hands-on learners.

Maybe you’ve asked a similar question. Here’s one way you can help your child get a literal feel for the planning stage.

First, he’ll need a lot of notecards—3×5 cards cut in halves or fourths work best—and a pencil.

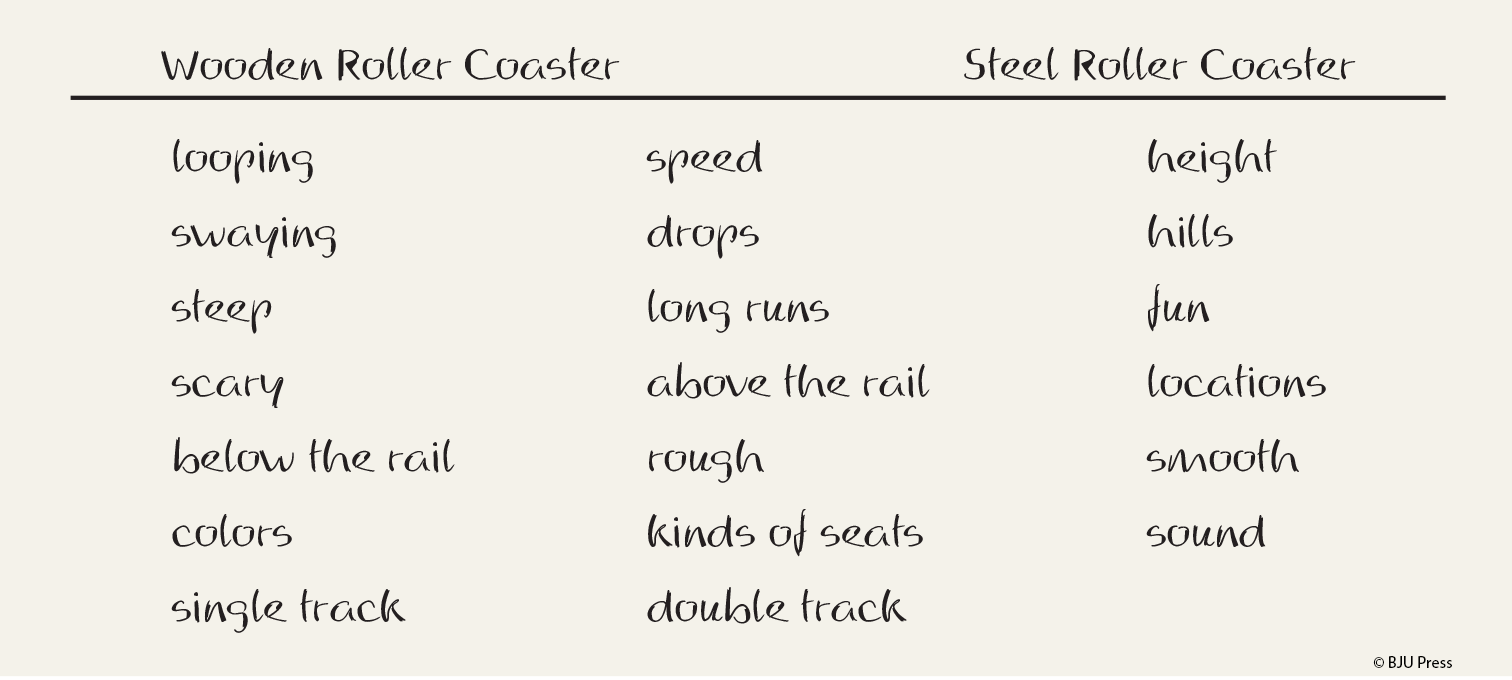

We’ll use the comparison-and-contrast essay and the sample brainstorming from chapter 3 of Writing & Grammar 12 as a foundation for this activity. (Example is from Student Worktext, page 64.)

Next, instead of making an ordinary list, have your child write each new idea he has about roller coasters (or whatever other topic he chooses) on a notecard.

Once he has a good number of cards (fifteen to twenty would be a good start), have him sort through his cards, putting all the items of a similar nature together in the same pile. For example, we can categorize items such as height, speed, rough, and smooth from the list above as physical characteristics.

After sorting the cards into piles according to categories, he should label the back of each card according to the category it belongs to.

He may find that one of his ideas can act like a category itself, like kinds of seats with our roller coaster brainstorming. Or he might realize that some ideas don’t fit into any of his categories. Suggest that he spend more time thinking through these cards, just in case there are other ideas that he could connect the loose cards to. If there’s nothing else, let him return to his larger categories.

With a comparison-and-contrast essay, as in our example, your child would need to sort his cards down further into the categories of the two items he’s comparing—in this case, wooden roller coasters and steel roller coasters. In a different kind of essay, these larger categories could represent different major points in the argument and would be separated into sub-points.

From here, your child needs to make sure of the purpose of his essay. If he’s decided to prove that steel roller coasters are more fun than wooden ones, then he should look through his cards to see which of his categories support his position.

Finally, it’s time to organize the cards according to their strength. In writing, we often conclude with the strongest point because information given last is what readers remember best. If he’s decided that his strongest argument rests on a physical characteristic, he should put his cards from that category at the bottom of the stack.

When brainstorming on notecards, it’s easy for your child to handle the information in a more literal sense. He can rearrange and recategorize his ideas as he needs to, without the hassle and mess of crossing out and erasing. He can also add additional notes or pictures to his cards, or whatever helps him manipulate the information.

All our Writing & Grammar textbooks include detailed explanations for the planning stage of each writing assignment, and many of them have varying suggestions for different kinds of learners. Check out our complete line here!

Leave a Reply